Note: From Jan to Feb 2018, the author worked as a researcher-in-residence at Kunci Cultural Studies Center, Yogyakarta, supported by NML Residency & Nusantara Archive Project. Yogyakarta has been the center of Indonesian arts and culture, with many independent cultural and art spaces established after 1998, providing alternative knowledge outside the academia. During the residency, the author investigated Kunci’s new “school” which is said to be inspired by Taman Siswa, an education movement and school founded in 1922 in Yogyakarta.Founded in 1922 in Yogyakarta, Indonesia, Taman Siswa was an alternative school to the Dutch colonial education system. Its teaching method is called “Among” (means ‘education’ in Javanese), which aims at cultivating students to move according to their natural character, to maintain freedom, peace and order of their body and soul. As such, the school not only taught general subjects such as language, science and economics but also traditional Javanese music and art. Taman Siswa did not set the pursuit of knowledge and enlightenment as its only and ultimate goal; rather, it simultaneously stressed the importance of feeling, thinking and experiencing in the process of developing nationalism, personality and culture. It is hard to imagine that, by 1930s and 1940s, Taman Siswa became home for many anti-colonial and nationalist activists and artists.

The founder of Taman Siswa, Ki Hadjar Dewantara (1889-1959), was born Soewardi Soerjaningrat in the royal family of Pakualaman in Yogyakarta. He was enrolled in the medical school STOVIA in Batavia (today’s Jakarta), but later became a journalist. At the same time, he actively participated in the political movement, joining the first political organization in the Dutch East Indies “Budi Otomo” which was established in 1908[1]. Ki Hadjar and two other friends founded the “Indische Partij” in 1912, attracted around 7000 multiracial members. However, it was soon banned by the Dutch authorities a few months later. One of the reasons behind was because of one Ki Hadjar’s article published in 1913, “If I Were a Dutchman”, in which he sarcastically criticized the colonial government for collecting money from the natives to fund the centennial anniversary of Dutch independence from France back in 1813.

“…What joy. What delight to be able to celebrate such an important national day! I wish I could temporarily be a Dutchman, not a nominal Dutchman but an unadulterated son of the Great Netherlands, free from any foreign blemish.”Towards the end of the article, he directly fired at the colonizer for humiliating the natives morally and materially.

“…Indeed if I were a Dutchman I would never celebrate the independence ceremony in a country which is still being colonized. I would first give the people whom we still colonize their independence, and then celebrate our independence.”[2]The three musketeers were exiled to the Netherland by 1913, still trying to continue their struggles there. Ki Hadjar entered a teacher training college, while working as a journalist. He even founded his own press bureau Indonesisch Pers-bureau.[3] For him, this was not only to connect the press bureaus in the Netherland and Dutch East Indies, but to convey the situation in the colonial land to the Dutch public, so as to prompt the colonizers to sympathize with the nationalist movement in Indonesia.[4] Soon, Ki Hadjar began interested in education and was inspired by the educational method and ideals advanced by Montessori and Rabindranath Tagore.[5] Few years after his return to the homeland, Ki Hadjar founded Taman Siswa, a school that allowed common people to receive education.[6] Not long after, he abandoned his royal title and changed his name to Ki Hadjar Dewantara – Ki denotes a man well respected for his knowledge; Hadjar means teacher; Dewantara is the mediator between higher realm and earth.

“Among” method, art education and “Wild School”

For Ki Hadjar, Dutch colonial education had been repressing children’s curiosity and creativity as it only meant to train submissive colonized citizens. Criticizing colonial education attitude which promoted intellectual, materialistic and individualistic method, Ki Hadjar raised the importance of cultural and political awareness in education, while believing that political movement alone couldn’t bring about national independence. As he said, independence and cultural autonomy were among the most important objectives when founded Taman Siswa.[7] In the school, he emphasized education of traditional music, dance and other art forms, enabling students to be able to express themselves. Notwithstanding, the anti-colonial Ki Hadjar was not entirely anti-West. Instead, he conjoined the knowledge and experience of both the East and West, looking for an appropriate localized knowledge system in Indonesia. Taman Siswa promoted a family-like, spontaneous learning method, and the teachers acted as guides instead of instructors who impose dogmatic knowledge on the children. The method was called “Among”, which derived from the Javanese word “Mong Ngemong”, meaning to educate the children. This method outlined an imagery picture: teachers standing behind the students, encouraging them to go forward; students autonomously going forward to learn and experience, but when they face challenges or obstruction, teachers would back them up (see picture below). This is not so much a teacher-student relationship, but, rather, a familial relationship.

Taman Siswa was also the first school in Indonesia to provide equal opportunity for women to receive education, which allowed civilian girls to enroll. On the very first year of its establishment, Taman Siswa’s women association was founded by Ki Hadjar’s wife Nyi Hadjar Dewantara (1890-1971) and fellow female teachers, aiming to promote women’s rights and related issues. Nyi Hadjar, born Startina Sasroningrat, was also from the Pakualaman royal family. Nyi Hadjar had been involving in journalism while promoting women’s rights; she and Taman Siswa’s teachers helped to hold the first National Women Congress in 1928.

Apart from that, as Taman Siswa put much emphasis on art education. Many Indonesian modern artists used to teach in Tawan Siswa, such as Sudjojono, Basuki Resobowo, Rusli, Alibasjah, Affandi, Trubus and Sindusisworo, to name a few. In 1949, Ki Hadjar and teachers from Taman Siswa helped founded Indonesia Art Academy (ASRI) in 1949, which later became Indonesian Institute of the Arts (ISI). As noted by Claire Holt, Taman Siswa had been crucial to the development of Indonesian modern art.[8] As can be clearly seen, Taman Siswa was not only an alternative school that promoted traditional education, but also a modern school with anticolonial features that had successfully gathered nationalists, women-right activists and a large number of artists.[9]

Such a place, of course, would not escape the colonizer’s attention. The Dutch enacted a “Wild School Ordinance” in 1932, demanding private schools to register with the authority, their teachers to submit teaching materials for the authority to control the “quality” of schools. That year, Taman Siswa already had 166 schools around the country, with 11,000 students. The ordinance was obviously targeted at Taman Siswa, thus Ki Hadjar forcefully resisted it with the support of his teachers and nationalists around Indonesia. The resistance had worked out, as the Dutch finally withdrew the ordinance after few months. Since then, Taman Siswa became an important symbol of local nationalism. Despite the fact that Ki Hadjar banned the teaching of politics in school and prohibited his teachers from participating political parties, many graduates of Taman Siswa joined politics after leaving school, and even became leaders in political parties.[10]

Taman Siswa in a Postcolonial Situation

As a native school embodying strong anti-colonial and nationalist spirit, Taman Siswa, however, had been facing difficulty in positioning itself after independence. Finally kicking out the Japanese imperialists and Dutch colonizers, it’s time to build up a system of “our own”. The question is – should Taman Siswa be nationalized? Or should it retain its uniqueness and independence? Two days after the surrender of Japan, Sukarno declared the nation’s independence and became the President of the Republic of Indonesia. Almost naturally, Ki Hadjar was appointed as the first Minister of Education under the presidential cabinet. He remained as a member of the Indonesian Education and Teaching Review Committee (PPPRI) after stepping down, in which he held strong opinion that nationalism and democracy should be significant elements of national education.[11]

At the same time, he saw the existence of private schools as important in a democratic nation. It is worth pondering over that, since Taman Siswa employed and promoted the spirit of traditional family values in its educational method and environment, could its school curriculum be incorporated into a national education system? Under the complex postcolonial situation, Taman Siswa was caught in a dilemma on the issues of nationalism and modernity. Franz Fanon said colonialism forces the colonized to ask themselves the question constantly: “In reality, who am I?”[12] If that is the case, Taman Siswa, being exposed to a postcolonial situation, was even harder to answer the question themselves after independence.

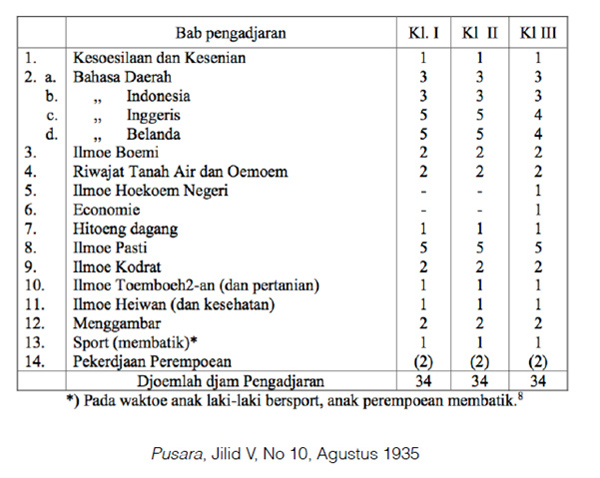

|

| 1935年學生樂園的課表, Courtesy of Antariksa |

In the 1950s and 1960s, Taman Siswa was involved in a tug-of-war debate between “traditional education” and “national education”. Scholars perceived Taman Siswa could no longer play a new and significant role in the new nation, but became a subordinate to national schools, only accepting drop-outs from other “normal” schools.[13] Simply put, the management of Taman Siswa was divided into two camps – the “progressive” and the “conservative”. The former believed that Taman Siswa had to move forward alongside the new nation’s system and to accept government subsidy; while the latter hoped to retain Taman Siswa’s tradition and independence. Eventually, the two factions came to an agreement that they would accept government subsidy “passively”, since Taman Siswa had been in need of financial assistance, but not actively requesting for it. In the 1952 Congress, the management agreed to drastically change the curriculum of primary and secondary schools (Taman Indira, Taman Muda and Taman Dewasa) to follow the national system, meaning that the students would take national examination and the schools would accept government teachers. Only the teaching-training Taman Guru would remain a separate entity. However, the solution did not solve Taman Siswa’s problem. As the students had to compete with students from normal schools in the national examination, their levels were obviously lower. Also, teachers graduated from Taman Guru were deemed as not professional, if compared to teachers from government schools who had “proper” training.

Thereupon, the conservatives asked, if such education system was so obsessed with intellectualism, but not the artistic exploration of students’ feeling, thinking and experience, what was the difference between such and the colonial system? They believed that Taman Siswa’s teachers were different in the sense of sacrifice, as they were unlike the educators who were trained by the national system to work for a job. Therefore, at the time of a left-inclined society in Indonesia, the conservatives deemed Taman Siswa as a unique entity in which labor union was not necessary, as it had no class system within. It might be useful to note Partha Chatterjee argument on how contradictory and complex nationalism is: it refuses the Western expression of colonialism, but in fact retains a basic belief of post-Enlightenment rationalism; this has led to the difficulty of constructing the postcolonial nation (especially the socialist ones) with indigenous knowledge.[14] As a result, while the new nation championed nationalism through modern and scientific education system, the existence of Taman Siswa became ambiguous.

At the same time, the young progressives in Taman Siswa were closely related to the Communist Party of Indonesia (PKI). The pro-communist faction in Taman Siswa saw the school’s ideals had been in line with Sukarno’s vision for the 1945 Indonesian constitution. In fact, the anti-colonial struggles of Taman Siswa had worked in the same pace with PKI, especially many of its teachers were members of Institute for the People's Culture (LEKRA), a literary and social movement associated with PKI. Only when the power relations in postcolonial Indonesia started to change subtly, Taman Siswa’s relationship with PKI was called into question. However, according to Kunci Cultural Studies Center’s co-founder Antariksa, who has been researching on the history of LEKRA, the pro-communist organization did not intend to “intervene” Taman Siswa, as they have different targets and goals. He said, after the war, those who could afford to enter Taman Siswa were predominantly Priyayi from the royal families, but not from the grassroots whom LEKRA was more concerned about.[15] I also had a chance to talk to Hersri Setiawan, a former political exile, also a LEKRA poet, who used to teach history at Taman Siswa. I asked how he and his comrades negotiate between the pro-communist ideology and the traditional values of Taman Siswa. His answer was simple: Taman Siswa had to maintain its uniqueness (‘ke-tamansiswaan’), and not be incorporated into the national education system.[16]

After Ki Hadjar passed away in 1959, pro-communist faction nearly won majority seats in the school’s congress in 1960. However, non-communist faction finally retained their dominant leadership.[17] From the hindsight, perhaps we could say this is considered “fortunate” for Taman Siswa as it managed to escape the aftermath of G30S. After the coup d’etat on Sep 30, 1965, Sukarno was overthrown and General Suharto would soon begin the anti-communist purge to create his New Order. During that time, Taman Siswa maintained its independence by declaring that it did not support any specific political party.[18] Until today, Taman Siswa is still an icon of independent education system throughout Indonesia. It even set up its own universities. However, how should it be perceived in contemporary times? Or, has it been transformed into other forms of knowledge and method, being manifested in contemporary Indonesian culture?

Rethinking alternative education: The practice of Kunci Cultural Studies Center

Alternative education is still very much discussed in contemporary Indonesia, especially in Yogyakarta, the birthplace of Taman Siswa. Yogyakarta is the cultural and artistic center of Indonesia; since the 1998 Reformasi movement, many independent art and cultural spaces emerged. They more or less have been unhappy with the national education system, hoping to create own independent sites of learning and practice. Founded in 1999, Kunci Cultural Studies Center is literally a product of Reformasi, as the two co-founders Antariksa and Nuraini Juliastuti were student activists who struggled to overthrow Suharto. After the regime change, freshly emancipated from a violent and rigid authoritarian system, they benefitted from the newly-minted, multidisciplinary discourse of “Cultural Studies”. Breaking through the oppressive political atmosphere, Kunci published regular newsletters, organized talks and workshops related to cultural studies, used interesting cultural theories to determine and decipher popular cultural phenomenon and society. Nevertheless, 20 years since Kunci’s inception, “Cultural Studies” or not seems not so important for the members nowadays. The question that lingers might be: how do they negotiate theory and practice, while continuing to play a role outside “proper” system?

In 2016, Kunci started a “School of Improper Education” (SoIE; it was named "Sekolah Salah Didik" in Bahasa Indonesia, literally “school of wrong education”). It aims at breaking the usual and so-called “proper” education, finding ways to create alternative learning methods. Kunci made an open call to the public, asking them to join this experimental “school”. They eventually formed a small group of about twenty participants, comprising of students, cultural workers, artists and social activists.[19] I arrived at Kunci in January 2018, by the time they had already experimented two learning methods – “Jacotot” and “Turba”. The first method came from French educational philosopher Joseph Jacotot (1770-1840), whose “emancipatory” method stresses that all men have equal intelligence, thus everyone can learn without a teacher. “Students” at the Kunci school, after several discussions, decided that they would learn sign language together without a teacher. However, none of them successfully learn the language eventually, after several “classes”. For SoIE participants, no learning is “failed”, and they are more concerned about the method and process of learning. The second method is “Turba”; the term derived from LEKRA’s “going to the ground” practice – turun ke bawah. SoIE members can decide themselves on how to go to the “ground”, what kind of “ground”, and how long it will take.

In the end, some went to the countryside to help the farmers, some became ride-hailing Go-jek drivers, some taught at religious schools, some participated in community work. Learning to live, work, and learn from different communities is a new thing for many of them. After Turba, they shared one another’s experience and observations, while evaluating the learning process among themselves. Different from LEKRA’s practice in the 1950s and 1960s, SoIE members may not have a leftist ideology or nationalist sentiments; their Turba practice is not to find inspiration or collect materials for their creative works. Instead, they put themselves into the situation that their Turba partners have been facing, while reflecting upon themselves who have grown up in “proper” education system, on how and what they learn from the real-life classroom.

There are two more methods SoIE will experiment in the future - “Nyantrik” and “Taman Siswa”. The former is a form of “commoning” lifestyle among craftsmen of Gamelan, the traditional Javanese instrument, where the masters and apprentices would live, work and create together.[20] The mentioned four learning methods have always been central issues to Kunci over the years, and the decision of using these four methods was made after several reading sessions and discussions during the planning of the school. According to Antariksa, they try to adhere to the learning methods as rigid as they can, then proceed to evaluate the feasibility and difficulty of adopting these historical methods in the present. When asked about how they are going to approach the method of “Taman Siswa”, he said they do not have a clear idea yet but just a vague direction. A clearer approach will be determined by each participant of SoIE. Usually, the so-called “classroom” is always a flexible and constantly shifting idea, as the classes would not only be held at Kunci but also other outdoor places as suggested by the members. This might already be the first step of the experiment, that is to establish a free and open learning environment that takes care of relationships and feelings among students just like how Taman Siswa did it before. During this process, they rethink about what and how to learn, and to what extend can knowledge shape and emancipate contemporary society.

As the “pioneer” of alternative education, Taman Siswa is still a living memory, one that creates special meaning to these young cultural workers. Somewhat similar to Taman Siswa which promoted traditional education, Kunci experiments four seemingly “outdated” learning method to retrieve the contemporaneity from history. This is not to simply retell history abruptly, nor does it try to prove the implication of history in contemporary time; instead, it is to look for a method to connect past and present, history and contemporary. That method is urgent, continuous and participatory, aiming to respond to problems that are local, collective and also urgent.

Footnotes:

1. Budi Otomo’s date of establishment, May 20, was declared as “National Awakening Day” in Indonesia after independence.

2. Quotes taken from A Well Respected Man, or Book of Echoes, edited by Binna Choi and Wendelien van Oldenborgh. Amsterdam: Casco/Sternberg Press, 2011, pp.60-66.

3. It has been said that Ki Hadjar was the first native to use “Indonesia” to refer to the region of today’s Indonesia. Thus, it is fair to say that politically he has never been Java-centric. He also advocated the use of Bahasa Melayu (Malay language), the common language in the Nusantara region, as the national language of Indonesia, instead of the majority Javanese. This vision has been continued in the later Taman Siswa (as the students had to learn Bahasa Melayu/Indonesia and a local language) and contemporary Indonesia’s national education system.

4. Kees van Dijk. The Netherlands Indies and the Great War, 1914-1918. Leiden: Brill, 2007, pp. 67.

5. During Tagore’s “Asian voyage” in 1927, he also visited Taman Siswa in Yogyakarta.

6. Before the establishment of Taman Siswa, Ki Hadjar and friends started a group called “Selasa Kliwon”. They met on every Tuesday of Kliwon (around 35 days in Javanese calendar), discussed about independence, education, Javenese thoughts, mysticism and other issues. Once Taman Siswa was created, the group was dissolved and the members became teachers in Taman Siswa. See Kenji Tsuchiya. “The Taman Siswa Movement: Its Early Eight Years and Javanese Background”. Journal of Southeast Asian Studies. 1975(6), pp. 164-177

7. Ki Hadjar Dewantara. Menuju Manusia Merdeka. Yogyakarta: Leutika, 2009, pp.63-74.

8. Claire Holt. Art in Indonesia: Continuities and Change. Ithaca: Cornel University Press, 1967,pp.195.

9. For different ideologies between Taman Siswa and other traditional schools, see Ruth McVey. “Taman Siswa and the Indonesian National Awakening". Indonesia. 1967(4), pp. 128-149.

10. George M. Kahin. Nationalism and Revolution in Indonesia. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1952, pp.88.

11. Ki Hadjar Dewantara. Menuju Manusia Merdeka. Yogyakarta: Leutika, 2009, pp.72-73.

12. Franz Fanon. The Wretched of Earth. Translated by Constance Farrington. New York: Grove Press, 1963, pp.250.

13. Lee Kam Hing. “The Taman Siswa in Postwar Indonesia”. Indonesia. 1978(25), pp. 41-59.

14. Partha Chatterjee. Nationalist Thought and the Colonial World: A Derivative Discourse. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1993, pp. 170.

15. Author’s interview with Antariksa on 12 Feb, 2018.

16. Author’s interview with Hersri Setiawan on 11 Feb, 2018.

17. see 13.

18. Soeratman. “Taman Siswa dalam masa proloognja G.30 S”. Pusara, Jilid XXVI. Nov-Dec 1965 (11,12), pp.6-12.

19. Chen Hsiang-wen. “The Wild School: KUNCI School of Improper Education”

20. Antariksa, “Nyantrik as Commoning“, in Kristi Monfries (ed.) The Instrument Builders Project: Hits from the Gong. Yogyakarta & Melbourne: The Instrument Builders Project, 2015, pp. 64-77.

沒有留言:

張貼留言