Hoo Fan Chon(符芳俊): Since I was little, and growing up in predominantly Chinese neighbourhood, I was puzzled by the concepts of “motherland” and “mother tongue” mentioned by elder members in the family. I didn’t quite know if they meant Malaysia or China at that time. My father would ask question related to national identity, for instance, if China badminton squad is competing against Malaysia, which team would I support? At the back of my mind, I had a feeling that he was hoping that I would root for team China. These thoughts have been playing in my head, just like my parents’ longing for the China, and China being the emerging world political power. Just like my last visit to Hainan island three years ago, where my grandfather came from, I could not relate to it as being home. There’s a huge gap between my way of thinking as compared to my dad’s. I regard myself as Malaysian first then only as Malaysian Chinese.

Tenn, Bun-ki: From my own observation, although there are differences between ethnic groups in Malaysia, the identity contradiction also exists among Malaysian Chinese. By asking more efficiently, I would like to know when was the time you got enlightened in the field of art? As I know, the five years of “Digital Media” you’ve majored in the University of Multimedia seem to focus more in “designing”.

HF: Yes indeed. Taking “Digital Media” as a major was a matter of assurance because I could cultivate creativity and learn the technical skills. Moreover, this was a more viable career path to my parents. After attended university, I was doing some web programming and worked at advertising firm. At the same time, I developed my interest toward photography especially street photography. The reason I went to the U.K. to study was to become a street photographer and make photograph like the ones I saw in National Geographic or The Lonely Planet. During my photography course, I was exposed to a whole bunch of discourses and theories, such as how image operates and photography was not what I understood it to be. I found another way to engage the medium, not only about the operation of image or photography as an ideological tool, and my art practice was not bound by the choice of medium. I didn’t know how this all started, but for me personally, the subject should always be the more important part of the work, then followed by chosen visual language to tell the story. Apart from photography, I also tried performance and sculpture making.

|

| Hoo Fan Chon, Still from ‘Carp leaping over the Dragon’s Gate’ (2008); image courtsy of artist |

There is piece which discusses how the middle class benefitted from the underground economy. My grandfather came to Pulau Ketam from Hainan at the time when national borders was not as strictly enforced. It was not so difficult for an outlander to enter into the country. I didn’t know how to engage a subject with such a huge theme, and I didn’t want to reduce the subject for the sake of artmaking. In the end, I chose to talk about the subject through a performance of me swimming across a canal during winter. I named the work "Carp leaping over the Dragon’s Gate", 2008. It is also a dish that can be ordered in chinatown. Perhaps due to the fact that I speak a few languages, it gave me different contextual entry points to words. I could have colloquial reference in Chinese and be more academic in English. Do you know that Carp leaping over the Dragon’s Gate is a folklore?

BT: Of course I do. However, your explanation reminded me of that when you interpreted for your own presentation on Co-Temporary forum, there were divergences in the text of translation. When you first said it in English and then translated it into Chinese (or vice versa), you would change a way of saying it. I guess it was because you master both languages.

|

| Pulau Ketam (2015); photo: Rikey |

HF: Or you could also say that during my presentation, as I was translating my presentation, new thoughts and ideas came to mind.

BT: You said that you wanted to become a Lonely Planet photographer. Does it reveal that you are not satisfied of living on an island? Have you ever been aware of how the island lifestyle make an impact on you?

HF: No, because I am from Kuala Lumpur not Penang. I used to yearn for “travel photography” this kind of life style. If you would like to define the relations between my life style and my dream work in that way, it perhaps has something to do with my hometown Pulau Ketam[1]. It is a small fishing village consist of only thousands of people. I was brought up there and my grandparents still live there. However, most of my relatives have moved out, and they only come back to visit during some festival holidays. My grandfather and my father went fishing there and also grew up there. I used to take care by my grandaunt and grew up in the village until I went to kindergarten. Later on, I spent my elementary school and middle school in the city. Nevertheless, I will go back to the island every year during long vacation.

BT: I thought that you were from Penang. Around year 2008, George Town was designated as World Cultural Heritage. In 2014, I participated Georgetown Festival in Penang, and it has already been very active and crowded. More than half of the art audience were from other places. Like I have noticed that the DA+C Art Festival curated by Suzy Sulaiman only brought in the market but was absent from the local community engagement.

HF: The decision to be based in Penang was due to personal reason. I never thought that I’d be staying for this long. Georgetown Festival has attracted many people’s attention and it provides opportunity and platform for cultural practitioners. Yet, local community are not the main target audience and some of the programmes might not have anything to do with the local history. This festival mobilises audience from the region and it is crucial to the cultural practitioners. However, as the hustle and bustle of the festival subsides, the rest of the 11 months are as equally important. I have mentioned in the presentation before that I always been more reactive than proactive when it comes to responding to the Penang cultural landscape, we never really had a clear general direction. What you saw during my presentation, is the first time I tried to map the Penang art ecosystem, what kind of resource do we have and these are the things I’ve never thought about before.

|

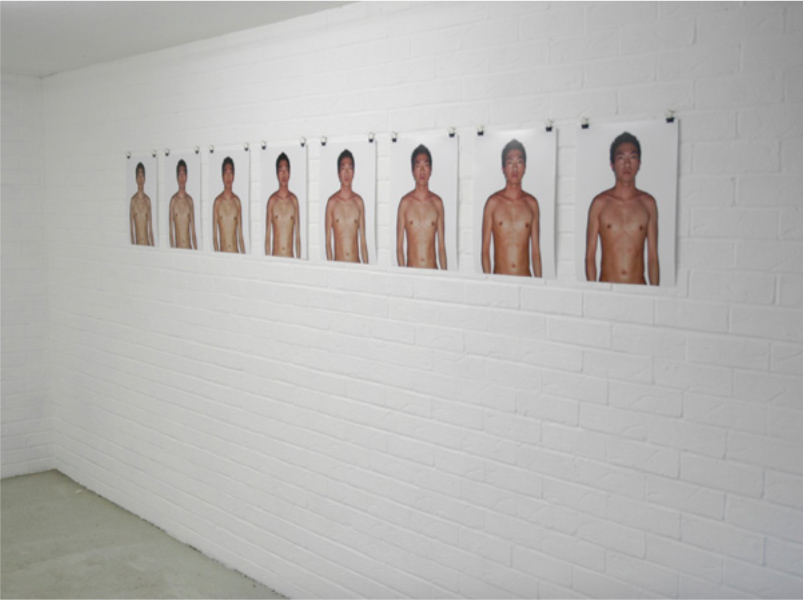

| Hoo Fan Chon, From Yellow to Red (2008); photo courtesy of artist |

BT: The early works of yours are very straightforward that enable the audience to reflect on social events or the themes related to the multiethnic society. "From Yellow to Red", 2009 is a very direct example.

HF: It was the first time I stayed in a country which colour sometimes is associated with ethnicity. In Malaysia, we don’t really joke with “skin tones”. When I was in the U.K., I have heard expressions such as brown persons, white persons, yellow persons. Of course due to political correctness, the terms are now less used. Personally, “red” symbolizes Chinese communism and “yellow” represents Chinese descents. These terms are for subtext reading and I don’t have to elaborate it. It is also good for the audience to make their own connections.

BT: For some of your works, we need to be able to think about the languages and forms that hide beneath , for instance "You say Jelly, I say Agar", 2010.

HF: The works you mentioned are all related to my growing up experience. If I have not gone abroad and lived overseas, I wouldn’t have another model or reference to the one I’m used to. "You say Jelly, I say Agar" came from my research on “Jelly”. During middle ages, only the noble class could afford to eat jelly. However, Jelly is a treat children get to eat during festive seasons back home, so I want to connect these two remote ideas together.

BT: There are pretty much the same elements recurring in your past experiences. Through connecting those two remote ideas, the eastern and western backgrounds of yours are highlighted. Yet the work “You say Jelly, I say Agar” is rather humorous than being sharply critical toward colonial issues.

HF: Humor is a great way for people to absorb information effortlessly. Jelly is cheap, colorful and not very nutritious. I made a collection of Jelly Sculpture, 2012 because I would to find out why British adopted certain forms in making jelly? Where do these forms come from? From the materials I found, the forms often suggest the shape of a castle. Based on that I started creating my own moulds and make jelly based on these.

|

| Hoo Fan Chon, The Blue and White Collection, article 7 - Gravy Pot (2010 -12); image courtesy of artist |

BT: Many of your works involve some particular backgrounds, such as inns or discos. Your collection of "The Blue and White stickon"[2] is somehow quite complicated which demonstrate by photography at last. You hope to simulate porcelain dishes by paper-made dishes in an auction manner of demonstration.

HF: I have a sense of skepticism towards photography. Perhaps I should put it this way, in my works, I often focus on the cultural identity, as well as the taste setting mechanism; Who decide what to wear? What is a superior culture? What is an inferior or bad culture? I am interested in people or things which they decide; how a banal object could be elevated into a cultural object of appreciation in another?

BT: I suppose the the construction of cultural tastes involves with "historical" and "geographical" factor, that is, the conversion of values that you have just mentioned. The misunderstanding may come from a romantic or oriental atmosphere. Just like in the past, the adventurer would search for treasures from the colonies and exhibit at home to fulfill the dream of possessing the world.The establishment of cultural tastes seems to contain these two parts. Sometimes it is not the matter of how rare the treasure is in the place of origin, but the collector’s desire to own the world and magnify his social status. It is like claiming cultural sovereignty, this makes me think of Wong Hai Cheong’s past discussions. Nevertheless, in your work, high art is just happen to be represented by the colonial culture, so it doesn’t have to be disassembled down the power relation of colonialism so seriously.

|

| Hoo Fan Chon, Keep Calm & Watch Youtube (political videos downloaded from YouTube & played back on tvs; 2013) |

I also found out the works of yours are often extended from the "food culture". For example, "You Say Jelly, I Say Agar is jelly", "The Blue and White stickon" is the tableware, "Keep Calm and Watch Youtube" , 2013 is inviting everybody to eat while watching the Internet.

HF: I didn’t pay attention to it, but I find the rituals and utensils related to "food" are very interesting. The kind of utensils you use will determine how people eat, how we conduct ourselves, and how etiquette works.

BT: Does this involves any cultural comparison? In my experience of art space residency in Southeast Asia, I didn’t pick it up when it comes to dining etiquette.

HF: Even it’s in the U.K., it also depends on the social situation. If you are dining with a group of artists in London, it can not be too formalised. I am describing the colonial period, people’s imagination of victorian era in the heyday of Britain that’s be practised and survived through time. It is unrealistic to apply that lifestyle on today’s modern society… I haven’t thought about it before. However, I guess you are right because I intend to do a diet-related project. There are a lot of pre-mixed instant coffee packet sold in Malaysia, and some of which contains aphrodisiac substance. Because is a common food product sold in regular coffee shops, therefore the packaging oftens employ a very direct visual symbols. I am interested in how the visual symbols are being used.

"The Blue and White stickon" series was layered in contexts, it should be my most photography-based work, it touches upon issues surrounding post-colonialism and my way towards photography. For instance cyanotype was a photographic technique used by botanists to study plants – a technique that could capture sillboute of the plants on photosensitive paper, it is also known as the blueprint. It is a concept about the original.[3] Is there such thing as an absolute original when it comes to culture? This is what I would like to explore. The Willow Pattern is an adapted and affordable version of Chinaware that has become a common household object in the U.K.

BT: This involves two kinds of questions on authenticity, one is the origin of culture, the other is the factuality of photography as a medium. – Have you ever thought of giving up running an art space? What about staying in London and try be a full-time artist?

HF: I do think about this a lot, especially when confronted with challenges within the collective. However a similar set of problems will ut if I chose to be an artist, problems still pop up in the art society we live. Although I have won the prize in the U.K. after graduation, I didn’t continue staying there.

I was very clear that I didn’t want to be an artist abroad. On the one hand, there are many things I can’t share value with, such as excessive Formalism. I believe that art and social politics are tightened, and the context is very important for the creation or the viewing. Once it is removed, the rest hardly make sense. On the other hand, being a Malaysian Chinese artist in U.K., I couldn’t find anyone to communicate with. Take the collection of “The Blue and White stickon” for instance, many curators asked me why the work appear so European rather than tropical? This question was raised to show that my personal background has been false interpreted. Southeast Asian culture is much more interesting, just like a book that never comes to an end. In fact, “The Blue and White stickon” aims at the British audience. It has already shown both in Korea and Malaysia, but the Malaysian audience didn’t seem to get what I was trying to convey.

BT: I also like the one you curated Fall into the Sea to Become an Island. The island here can be referred to Pulau Pinang or Pulau Ketam, same as what we focus on, and it shows your sense of humor and sensitivity. The other works of yours follow this naming logic as well.

HF: It seems like I always witness things right after I intended to do it. I hope I can explain what I am doing to my family simply with a sentence. Yet, if everyone would like to discuss from different perspectives, I would love to elaborate more. The concept of Fall into the Sea and Become an Island group exhibition came from the installation outside of the exhibition, an observatory-to-be on the artificial island (Pulau Korea) next to Penang Bridge where people could gaze back after leaving Pulau Pinang. However, the land office didn’t approve the construction at last due to security considerations. The original design of the observatory is Malay architecture. I hope that the exhibition encourages people to discuss about this.

BT: I would like to ask how to think about the "region/place" from the notion of the "space"; and also about the act you have done in 2013 to invite everyone to watch the campaign video in Run Amok.

HF: I had this idea in mind since 2013, but it was until 15 days before the election did the ruling party announced the date.

At that time, I gathered many TVs as soon as I could and madly downloaded all the youtube videos from every campaign parties because I wanted to do a Archive project. I had no idea when this project would end since there were so many promos and slander videos coming up from every parties. I hoped to add some fun factors into these images because the election has messed up everyone in anxiety, just like the “panic room” we said in English. You came here to watch my archive and became even more panic. In Run Amok, we offered karaoke upstairs, you could sing any patriotic songs you had in mind. We had a beverage stand as well. You see, in Malaysia the amount of unhealthy colored beverage you took in were beyond your imagination. However, the colors were as well so rich that we were able to use different colors to make our own cocktail, representing the color of the party we supported.

In 2013, I was still exploring the city of Penang, getting to know the artists in Malaysia, and pondering the way to head to. Liew Kwai Fei was the first friend we made in art circle. Trevor and I bought his artwork at first and then invited him to join the exhibition in Run Amok after getting to know him more. Later on, he had his solo exhibition in Run Amok. Liew Kwai Fei and Kuik Ching Chieh is a couple living in Rawang. After they became the members of Run Amok, another painter Hasanul Isyraf Idris and his wife, Tetriana Ahmed Fauzi, who teach at the only university in Penang, also attended our activities. We formalised as a collective because they often come to participant and I was tie up with my new job at Fergana Art. We asked them if they were willing to join us without getting payment and detail assignment. Basically, Trevor and I are in charge of administration duties, Kwai Fei and Hasanul curate exhibitions from time to time, Tetriana sometimes prepares food for opening receptions. Our plan is to operate Run Amok (space) with community instead of individuals. Ideally, the core members should be more flexible with their time in running the space, however, they are under great pressure because they need to focus on their studio works. You have been asking me if I want to concentrate on artmaking, my answer is, “We may be a bit similar to Open Contemporary Art Center!”

When I saw Cemeti Art House representative on Co-Temporary, it encouraged me to keep faith although the background of Yogyakarta is different from Penang. I even expect a member of ours become an instant hit and sell a lot of paintings to support Run Amok. Of course I can now answer you I have the confidence to keep the space running, but at the very beginning I only promised myself not to quit until ten exhibitions were out. By far, there are over ten exhibitions already. Run Amok is now owned by a group of people not just me, so I can’t quit only because I don’t feel like doing it. The space depends on every members, and I need to be responsible for all. Therefore, I am still thinking if there is possibility that we attempt to do collective curatorial or collective creation. Well, the second option has been rejected. I know if Trevor is not convinced by the value of “collectivism”, he will not support me devoting this much unconditionally.

Lastly, I am still in the state of realizing what exactly “Artist in Residence” stands for. I don’t think it is an essential form of art making ,and I am still trying to figure out how to do it. How one evokes another through residency either in terms of creating or experience exchanging? If the organizer is incapable to assist artist to have a better picture about local knowledge, then I don’t really see the practicality of residency.

Endnotes:

1. Ketam means “crab” in Bahasa Melayu.

2. See the feature report on premiere issue of Voices of Photography

3. Like the Victorian female botanist Anna Atkins (1799~1871).

沒有留言:

張貼留言